Welcome to SavingIceland.org! Read the S.O.S. and About SI section if you are new to our site. Iceland Under Threat shows the wilderness we need to protect and the corporations bent on ruining it. Make sure to enjoy our video and photo galleries, our in-depth magazine Voices of the Wilderness and subscribe to our mailinglist and follow our Twitter feed to keep up to date.

Welcome!

Feb 20 2017

1 Comment

‘A nice place to work in’? Experiences of Icelandic Aluminium Smelter Employees

A special report for Saving Iceland by Miriam Rose

In 1969 the first of three aluminium smelters was built in Iceland at Straumsvík, near Hafnafjörður, on the South West side of Reykjavík by Alusuisse (subsequently Rio Tinto-Alcan). In 1998 a second smelter was constructed by Century Aluminum (now a subsidiary of controversial mining giant Glencore), at Hvalfjörður near Reykjavík, and in 2007 the third, run by Alcoa, was completed at Reyðarfjörður in the remotely populated East of the country. The Icelandic Government had been advertising the country’s vast ‘untapped’ hydroelectric and geothermal energy at ‘the lowest prices in Europe’ hoping to attract jobs and industry to boost Iceland’s already very wealthy but somewhat fishing dependent economy. The industry, which would permanently change Iceland’s landscape with mega-dams, heavy industry scale geothermal plants and several kilometer long factories, was promoted by the Icelandic Government and the aluminium companies as ‘good employment for a modern age’. However, ten years after the flagship Alcoa Fjarðaál project was completed, unemployment is higher than it was in 2005, and Iceland’s economy has become dependent on an industry which is vulnerable to commodity cycle slumps and mass job losses. Worse, the price charged for Iceland’s energy is tied to the price of aluminium and analyses of the country’s 2008/9 economic crisis suggest it was exacerbated by the poor terms of Iceland’s late industrialisation. Yet demands for further industrialisation remain, and more than 1000 Icelanders are employed in the aluminium sector.

This article exposes the conditions inside Iceland’s aluminium smelters based on interviews with workers conducted in 2012. The stories from two smelters share correlating accounts of being forced to work in dangerous conditions under extreme pressure, and without adequate safety equipment, leading to serious accidents which are falsely reported by the companies. These shocking allegations require serious attention by the trade unions, Icelandic government and health and safety authorities. This especially in the current context of labour disputes with the aluminium companies, alongside revelations about the same companies’ tax avoidance schemes and profiteering in the country. Read More

An Uncertain Alternative

Árni Daníel Júlíusson

Iceland’s recent general election shows that the country’s neoliberal consensus is over. What happens next?

When the Icelandic parliament assembled in fall of 2010, tens of thousands gathered to throw eggs and rotten tomatoes at the politicians. The MPs were participating in a traditional march between the cathedral and the parliament building that marks the beginning of each legislative setting. Protesters repeated their performance exactly a year later, now with an even larger crowd.

These events marked the midpoint of Iceland’s anti-neoliberal rebellion, which had started in the fall of 2008 at the time of the financial collapse. The mass actions represented a definitive break with the neoliberal consensus the country had sustained since 1984.

Any government will now have to understand — and then accept — this popular revolt if it wants to credibly hold power. Old alliances and structures have collapsed, and new ones must be built.

This October’s elections reflected the changed political atmosphere. On the one hand, the results were inconclusive, failing to produce a clear majority that could form a government. On the other hand, they decisively showed the fate of the sitting government, made up of the centrist Progressive Party (FSF) and the right-wing Independence Party (XD). In 2013, they had received a clear majority of votes — each winning nineteen parliamentary seats out of a total of sixty-three — despite their direct responsibility for a number of bank collapses in 2008.

Between 1991 and 2008, XD enacted a unrelenting series of ultra-neoliberal and right-wing policies that led to the financial crisis. The basis for this neoliberal turn, however, was laid in the eighties, when an earlier Progressive-Independence coalition government held power.

How these parties returned to power in 2013 can only be explained by the events between the financial crisis and that election. Their fate in this October’s election gives us a sense of what might come next.

A Disgraced Left

When the Icelandic banks collapsed on October 6, 2008, a powerful mass movement appeared out of nowhere. By late November, it had become a grave threat to the government.

The movement was organized on several levels and had several centers of operations, which were mostly uncoordinated. All of them coalesced, however, in weekly meetings in the center of Reykjavík. On December 1, protesters convened a meeting at Arnarhóll, after which the more radical wing attacked and occupied the Central Bank of Iceland. A full-scale uprising — which many expected — did not materialize. Read More

Nov 21 2015

4 Comments

Armand, Our Legendary Dutch Singer Friend has Died

Armand, the famous Dutch protest singer and a great friend and supporter of Saving Iceland, died on 19 November at 69 years.

Saving Iceland remember him with great affection and gratitude for his friendship and his love of Icelandic nature.

Armand, whose name was George Herman van Loenhout, only spent two days in hospital with pneumonia before he died. Since childhood he had suffered from asthma and was not expected to live beyond 20. Hence Armand called “every day a bonus.” “I’ve already had 49 additional years, so I can not complain,” he said earlier this year.

During a career lasting fifty years Armand wrote and recorded at least eleven solo studio albums and dozens of singles. One of his greatest hits was “Ben ik te min” (Am I not worthy?) which stayed for 14 weeks in the Dutch Top 40 in 1967. Armand was writing and performing to the very last. Some recent collaborations were with young Hip-Hop artists Nina feat Ali B & Brownie Dutch, and recordings and performances with Dutch band De Kik.

Armand traveled extensively around Iceland and wrote several songs in support of the fight against the corporate energy projects and heavy industry endangering the Icelandic environment. For us here in Saving Iceland it was a real privilege to witness the professional way in which he approached the writing of his lyrics and his genuine concern for accuracy and proper research of the Icelandic situation. Not to mention his warmth and humour, and irreverence for authority.

Although it is with great sadness that we salute our dear friend Armand, we can proudly testify that he lived a life full of song and colour, and that he was an inspiration to generations.

Armand’s music for Iceland:

Brave Cops of Iceland: Download

Ísland, ég elska þig. Ofwel: IJsland, ik hou van jou: Download

European Affair: Download

Jul 30 2015

2 Comments

Time to Occupy the Smelters?

Helga Katrín Tryggvadóttir

Icelanders are notoriously bad investors. Once someone has a business idea, everyone jumps on the wagon and invests in exactly the same thing. The infamous growth of the banking sector is one example, before the 2008 banking crash the Icelandic banking sector was 12 times the size of the GDP and Iceland was supposed to become an international financial centre. I have no idea how anyone got the idea that an island with three hundred thousand inhabitants could become an international financial centre, but many people in Iceland considered this a perfectly normal ambition.

And then there are the politicians, they have had the same investment idea for more than hundred years. Either it is building an artificial fertiliser factory, or it is building an aluminium smelter. Last year one MP proposed building an artificial fertiliser factory, in order to “lure home” young Icelanders who have moved abroad. A majority of those have moved abroad to educate themselves, but sure, who doesn’t want to use their PhD on the factory floor?

Now there is an Icelandic investor in the North of Iceland, Ingvar Skúlason, who is planning on building an aluminium smelter, at a time when aluminium prices have been dropping due to overproduction. He has already managed to sign a deal with a Chinese company, NFC, which is willing, he says, to pay for the whole construction, yet the smelter would be owned by Icelandic companies. All of this sounds kind of dubious in my ears. And everyone can see that this is not a good idea, even the banks, with a new report released by Arion Bank advising against more investment in the aluminium industry. The bank bases its analysis on the fact that aluminium price is too low at the moment to bring any profit into the country (since the price for the electricity is connected with the price of aluminium, the price the aluminium smelters pay to the National power company (LV) is low when aluminium prices are low).

But that does not stop the politicians from supporting the idea. The prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, was present when Skúlason signed a deal with the Chinese company, praising the initiative. Skúlason also claims to have support from the Minister of Industry, which is not surprising since her only campaign promise was building an aluminium smelter and get the “wheels of the economy rolling”. Recently, Alcoa World Alumina, owned by Alcoa Inc., admitted to having bribed officials in Barein. In Iceland, however, they have never had to pay any bribes. Icelandic officials have been more than willing to do their service for free, “bending all the rules” as Friðrik Sophusson, former head of LV, was caught on tape saying.

There are currently three aluminium smelters in Iceland. Together, they use 80% of the energy produced in the country and their profit account for 60 billion ISK a year (USD 500 million). Yet, a majority of the profit is registered as debt to their parent companies abroad, leaving the Icelandic subsidiaries operated in debt but creating profits to the parent companies. The only profit that is left in the country is the wages they pay to their employees, and that only accounts to less than 1% of the national revenue. The jobs they create (which is usually the main argument for their construction), also account for less than 1% of all jobs in Iceland. The price they pay for the energy is also below the normal market price. Lets think about this for a second: 80% of the electricity produced in the country goes to international corporations that only produce 1% of the national revenue and creates 1% of the jobs, exports the majority of the profits and pays below-market price for the energy. So, 99% of the people do not get any share in the majority of its electricity production. Sounds familiar.

Maybe it is time to occupy the smelters?

Does Living Next to a Geothermal Power Plant Increase Your Risk of Dying?

In a recent report published in the Lancet it is claimed that switching to “clean energy” from fossil fuels will not only have beneficial effects on the environment, but also on people’s health since carbon intensive energy technologies simultaneously produce air pollution. According to the Salon, the report estimates that air pollution from the UK’s power sector is responsible for 3800 premature deaths per year. In order to combat this we are encouraged to transition to low-carbon energy technologies. That is all fine and well, but what low-carbon technologies are we talking about exactly?

Currently, the Icelandic National Power Company, Landsvirkjun (LV) is discussing the possibility of selling “clean” and “renewable” electricity to the UK via submarine cable and, as far as we are informed, some investors are interested in the plan. Almost 100% of Icelandic electricity is generally classified as renewable energy and therefore viewed as “low carbon” or “clean energy”.

There has been heated debate in Iceland surrounding further exploitation of its energy sources, which has led to the creation of an Energy Master Plan, which is supposedly to create consensus on the exploitation of hydropower and geothermal energy. Out of 25 of the highest ranking energy options, 21 are geothermal power plants. Constructions and plans for most of them is already underway.

The problem is that Geothermal Energy is not as “clean” as many would think, even though it is classified both as low carbon and renewable energy source. In fact, the production of electricity through the use of geothermal energy accounts to around 8 – 16% of Iceland’s CO2 release. However, Icelandic authorities do not consider those emissions anthropogenic and therefore do not count them as part of the country’s overall emissions.

A recent research by Ragnhildur Finnbjörnsdóttir, shows a correlation between increased numbers of death in Reykjavík and increased levels of hydrogen sulphide (H2S) from geothermal plants. The research was conducted between 2003 and 2009, and shows a 2-5% increase in deaths shortly after elevated levels of hydrogen sulphur. According to Finnbjörnsdóttir, hydrogen sulphur does not necessarily lead to any specific disease, but increases the seriousness of diseases people already suffer from.

Geothermal power plants emit hydrogen-sulphide (H2S), which is both corrosive and very toxic. H2S forms sulphur-dioxide (SO2) in the atmosphere, which can cause respiratory problems and asthma, as well as acid rain. From 1999 to 2012, the levels of SO2 in the Reykjavík area have risen by 71%. and in 2012, 80% of the SO2 released in Iceland came from Geothermal power plants.

In 2013 it was estimated that a year later the geothermal power plant in Hellisheiði, around 30 km from Reykjavík, would not be able to control H2S release under health regulation standards. Exact figures of H2S release from the power plant have not been released and due to a long standing volcanic eruption in Holuhraun in 2014, SO2 levels were elevated throughout the whole year, with the levels of SO2 at times reaching such levels that people tried their best to stay indoors.

More research on the health impact of SO2 from geothermal plants is needed, but a correlation between medicine costs and SO2 levels has already been established. In a 2010 study, Carlssen shows that in easterly winds in Reykjavík (blowing from the geothermal plant towards the city), medication costs rise by 2%.

In addition to the medical costs, the SO2 levels also lead to increased corrosion of metals, increasing the costs of replacement of circuit boards and other complicated electronics.

“Countries could quickly and economically reduce air pollution and its direct impacts on public health by transitioning to low-carbon energy technologies”

says the Lancet report. However, I do not recommend switching to geothermal energy if we are to avoid pollution-related deaths.

Read More

Majority Pushes For Eight New Hydro Power Plant Options

Proposal and lack of due process called “unlawful” and “declaration of war”

Last week’s Thursday, the majority of Alþingi’s Industrial Affairs Committee (AIAC) announced its intention to to re-categorize eight sites as “utilizable” options for the construction of hydroelectric power plants. These have until now been categorized, either as for preservation, or as on “standby”. These are categories defined by the Master Plan for nature conservation and utilization of energy resources, as bound by law. The re-categorization would serve as the first legal step towards potential construction.

The proposal had neither been announced on the committee’s schedule, before its introduction, nor introduced in writing beforehand. The committee’s majority gave interested parties a week’s notice to submit comments on the proposal, which is admittedly faster than we managed to report on it.

Reasoning

When asked, by Vísir, why the proposal was made with such haste, without any prior process in the committee or an open, public debate, Jón Gunnarsson, chair of the committee on behalf of the Independence party, replied that “it is simply about time to express the majority’s intention to increase the number of options for utilization.”

The proposal is in accordance with statements made by the Minister of Industry, Ragnheiður Elín Árnadóttir, at Landsvirkjun’s autumn meeting earlier that week, as reported by Kjarninn. In her speech at the occasion the Minister said: “I will speak frankly. I think it is urgent that we move on to new options for energy development, in addition to our current electricity production, whether that is in hydropower, geothermal or wind power. I think there are valid resons to re-categorize more power plant options as utilizable.”

Opposition

As the proposal was introduced to Alþingi, members of the opposition rose against the plans.

Róbert Marshall, Alþingi member in opposition on behalf of Bright Future, has called the lack of process “deadly serious” and “a war declaration against the preservation of nature in the country”. Steingrímur J. Sigfússon, the Left-Greens’ former Financial Minister, concurred, calling the proposal the end of peace over the topic, as did the former Environmental Minister on behalf of the Left-Greens, Svandís Svavarsdóttir, who called the proposal “a determined declaration of war”. Katrín Júlíusdóttir, former Minister of Industry, on behalf of the Social-Democrats’ Coalition commented that the proposal was obviously not a “private jest” of the committee’s chair, but clearly orchestrated by the government as such.

Lilja Rafney Magnúsdóttir, the Left-Greens’ representative in AIAC, and the committee’s vice chair, condemned the proposal. According to her, Minister of the Environment, Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, specifically requested fast proposals on these eight options. She says that she considered the data available on all options to be insufficient, except for the potential plant at Hvammur.

That same Thursday, the Icelandic Environment Association (Landvernd), released a statement, opposing the proposal. According to Landvernd’s statement, five of the eight options have were not processed in accordance with law. Landvernd says that the proposal “constitutes a serious breach of attempts to reach a consensus over the utilization of the country’s energy resources.” It furthermore claims that the AIAC’s majority thereby goes against the Master Plan’s intention and main goals.

Landsvernd’s board says that if Alþingi agrees on the proposal, any and all decisions deriving thereof will “constitute a legal offense and should be considered null and void”. Guðmundur Ingi Guðbrandsson, Landvernd’s manager, has since stated that if the plans will proceed, the high lands of Iceland will become a completely different sort of place.

The Iceland Nature Conservation Association (INCA) also opposes the plans. The association released a statement, pointing out that if current ministers or members of Alþingi oppose the Master Plan legislation, they must propose an amendment to the law, but, until then, adhere to law as it is.

The options

Mid-October, Environmental Minister Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson already proposed re-categorizing one of the eight areas, “the plant option in Hvammur”, as utilizable. This was in accordance with proposals made by AIAC last March. Leaders of the parties in opposition then objected to the decision-making process, saying that such proposals should be processed by Alþingi’s Environmental Committee before being put to vote. The Hvammar plant would produce 20 MW of power.

The other seven options to be re-catogorized are: the lagoon Hágöngulón (two options, totalling 135 MW); Skrokkalda, also related to Hágöngulón (45 MW); the river Hólmsá by Atley (65 MW); lake Hagavatn (20 MW), the waterfall Urriðafoss (140 MW); and Holt (57 MW).

The last two, as well as the plant at Hvammur, would all harvest the river Þjórsá, the country’s longest river. The eight options total at 555 MW.

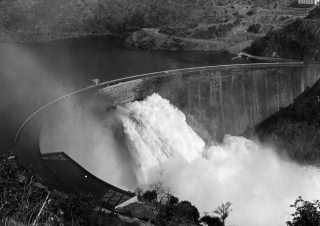

Backstory: Kárahnjúkar

The latest power plant construction in Iceland took place at Kárahnjúkar. The 690 MW hydropower plant at Kárahnjúkar is the largest of its type in Europe. It fuels Alcoa’s aluminum smelter in Reyðarfjörður. The largest power plant in the country before Kárahnjúkar, was the Búrfell hydropower plant, on-line since 1969, at 270 MW. The Icelandic government and the national power company Landsvirkjun committed to the dam’s construction in 2002, which was concluded in 2008. The total cost of the construction was around USD 1.3 billion. The largest contractor was the Italian firm Impregilo. The construction was heavily contested, for its environmental and economic effects, for the treatment of the workers involved and for a lack of transparency and accountability during the prior decision- and policy-making process.

At least four workers were killed in accidents on site, and scores were injured. “I have worked on dam projects all over the world and no-one has even been killed on any of the schemes. To have this number of incidents on a site is not usual,” commented International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD) vice president Dr Andy Hughes at the time.

During the construction, the country saw new kinds of protest actions, involving civil disobedience and direct action, led by the organization Saving Iceland. Andri Snær Magnason’s 2006 book Draumalandið – The Dream Land – contesting Iceland’s energy policies, and calling for a reinvigorated environmentalism, became a bestseller at the time. Ómar Ragnarsson, a beloved entertainer and TV journalist for decades, resigned from his work at State broadcaster RÚV to focus on documenting the environmental effects of the Kárahnjúkar plant and campaigning against further construction on that scale. Read More

Is Fluoride Hurting Iceland’s Farm Animals?

Al Jazeera

Some farmers suspect fluoride from aluminium smelters is making animals sick, but the companies sharply disagree.

Reykjavik, Iceland – For the third summer in a row, hydrogen fluoride has been detected in vegetation samples taken near an aluminium plant in eastern Iceland, worrying farmers and horse owners who fear for their animals’ well-being.

Aluminium plants emit fluoride, a chemical element that can be toxic to animals and humans in high concentrations.

The Environment Agency of Iceland found the concentration of fluoride in grass grazed by sheep exceeded the recommended limits near the town of Reydarfjordur.

Sigridur Kristjansdottir from the Environment Agency told Al Jazeera the high levels this summer were “primarily due to meteorological and geographical factors … This resulted in the results for early June showing relatively high values”.

A press release issued by the Alcoa Fjardaal aluminium plant noted that, despite the spike this summer, average fluoride levels this year are lower than they were in 2013, which in turn were lower than in 2012.

Fluoride is a cumulative poison, meaning that animals and plants often register higher levels of the element as they age. Before the Fjardaal aluminium smelter began operation, the fluoride level in Sigurdur Baldursson’s sheep – who live on the only farm near Alcoa’s plant – were measured as having 800 micrograms per gram (µg/g) of fluoride in their bone ash. That’s well below the recommended limit of 4,000 µg/g in the bone ash of adult sheep, or 2,000 µg/g for lambs.

But samples taken in 2013, recorded the sheep’s fluoride levels between 3,300 and 4,000 µg/g. Baldursson said he expects the next readings to exceed 5,000 µg/g – above the recommended limit.

“The sheep that will be sampled next were born in 2007, and are thus as old as the aluminium plant itself,” he told Al Jazeera.

Nevertheless, Baldursson said he has not noticed signs of ill health in his sheep.

‘I only heard about it by accident’

Bergthora Andresdottir sees things differently from her farm on the other side of Iceland, 25km north of the capital Reykjavik. She said she is constantly phoning the Environment Agency to complain about smoke rising from Century Aluminium’s smelter at Grundartangi, directly across the fjord from her farm.

“I phone them several times a week,” she told Al Jazeera. “But there’s no specific person to talk to, and they don’t help much. Sometimes they claim that the smoke is coming from the neighbouring factory [the Elkem ferrosilicon smelter], but I tell them it isn’t.”

In August 2006, an accident at the Grundartangi plant caused a large amount of fluoride emissions. Riding school owner Ragnheidur Thorgrimsdottir said local farmers were never told about this accident, which meant that sheep, cattle and horses ate fluoride-contaminated grass. “I only heard about it by accident, two years later,” she told Al Jazeera.

That same year, the capacity of the Century plant was increased from 90,000 tonnes of aluminium a year to 220,000. The firm HRV Engineering stated “the increase in fluoride for the autumn months of 2006 in the atmosphere … can partly be traced to the increase in capacity of the smelter”.

Sick horses

Thorgrimsdottir lives about five kilometres southwest of the Grundartangi plant, and owns 20 horses – which she said have been badly affected by fluoride, some so badly that they have had to be put down.

“This is the eighth year in a row that my horses have been sick. Currently three of them are sick, but I’m also keeping an eye on four more,” she told Al Jazeera. Instead of keeping her horses outside all the time, as is the norm during Icelandic summers, she has kept them in at night and given them hay to eat because they do not digest grass properly.

Thorgrimsdottir showed Al Jazeera one of the affected horses named Silfursteinn. “The affected horses walk stiffly, like sticks. They also tend to have lumps and swellings on their bodies,” said Thorgrimsdottir.

When asked about Thorgrimsdottir’s horses, Solveig Bergmann – a public relations officer for Century – said she could not explain their maladies. “I have no explanation. According to veterinarians, the horses … bear symptoms of Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS), which is caused mainly by obesity and lack of exercise,” she said, citing a report by the Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority (IFVA).

But Thorgrimsdottir said EMS can also be caused by fluoride, and when IFVA vets took samples from the horses she had to put down, they only measured fluoride levels in their bones, not in their soft tissue as she had requested.

Gyda S Bjornsdottir studied the birth rates and health of sheep from 2007 to 2012 in the area close to the Grundartangi plant for her Master’s degree. She found in the areas southwest and northeast of the smelter – which are the most common wind directions in the region – a higher proportion of sheep did not produce any lambs.

“Usually, two to three percent of sheep do not produce lambs. Away from the plant, 2.6 percent of ewes were lambless, whereas in the area southwest of the plant, this figure was 7.4 percent,” she told Al Jazeera. Northeast of the plant, she added, 4.5 percent of ewes did not bear lambs.

“The sheep in the area to the southwest of the plant also show visible signs of tooth damage, which is a clear sign of fluoride poisoning, and poor quality wool,” said Bjornsdottir.

Because the aluminium smelter is next to a ferrosilicon plant that also emits pollutants, Bjornsdottir said she cannot be sure the effects are caused by fluoride, as there were also increased concentrations of sulphur dioxide, nickel and arsenic.

“But the results are consistent with fluoride distribution,” she said.

‘No evidence’ of negative effects

But Bergmann, the Century public relations officer, disagreed. “In research carried out since 1997 in the vicinity of the Century Aluminium smelter at Grundartangi, no evidence has ever been found of negative effects of fluoride on sheep, or any other animal,” she said.

Bjornsdottir, however, pointed out in her thesis that farmers say it is not economically viable to send sick sheep to a veterinarian. Instead, they slaughter the affected sheep at home. As a result, she said she believes the figures are biased, because the sheep monitored by Century for fluoride are healthy animals that are sent to the slaughterhouse.

In a letter sent by Iceland’s Food and Veterinary Authority to Alcoa in January 2013, Thorsteinn Olafsson – who was responsible for sheep and cattle diseases at that time – said: “There are reasons to suppose that the danger levels for grazing and fodder for Icelandic sheep are even lower than overseas research shows. This needs to be researched even better in the local environment of aluminium plants in Iceland.”

Source: Al Jazeera

See also Hand in Hand: Aluminium Smelters and Fluoride Pollution

Large Dams Just Aren’t Worth the Cost

By Jacques Leslie

Sunday Review

New York Times

Thayer Scudder, the world’s leading authority on the impact of dams on poor people, has changed his mind about dams.

A frequent consultant on large dam projects, Mr. Scudder held out hope through most of his 58-year career that the poverty relief delivered by a properly constructed and managed dam would outweigh the social and environmental damage it caused. Now, at age 84, he has concluded that large dams not only aren’t worth their cost, but that many currently under construction “will have disastrous environmental and socio-economic consequences,” as he wrote in a recent email.

Mr. Scudder, an emeritus anthropology professor at the California Institute of Technology, describes his disillusionment with dams as gradual. He was a dam proponent when he began his first research project in 1956, documenting the impact of forced resettlement on 57,000 Tonga people in the Gwembe Valley of present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe. Construction of the Kariba Dam, which relied on what was then the largest loan in the World Bank’s history, required the Tonga to move from their ancestral homes along the Zambezi River to infertile land downstream. Mr. Scudder has been tracking their disintegration ever since.

Once cohesive and self-sufficient, the Tonga are troubled by intermittent hunger, rampant alcoholism and astronomical unemployment. Desperate for income, some have resorted to illegal drug cultivation and smuggling, elephant poaching, pimping and prostitution. Villagers still lack electricity.

Mr. Scudder’s most recent stint as a consultant, on the Nam Theun 2 Dam in Laos, delivered his final disappointment. He and two fellow advisers supported the project because it required the dam’s funders to carry out programs that would leave people displaced by the dam in better shape than before the project started. But the dam was finished in 2010, and the programs’ goals remain unmet. Meanwhile, the dam’s three owners are considering turning over all responsibilities to the Laotian government — “too soon,” Mr. Scudder said in an interview. “The government wants to build 60 dams over the next 20 or 30 years, and at the moment it doesn’t have the capacity to deal with environmental and social impacts for any single one of them.

“Nam Theun 2 confirmed my longstanding suspicion that the task of building a large dam is just too complex and too damaging to priceless natural resources,” he said. He now thinks his most significant accomplishment was not improving a dam, but stopping one: He led a 1992 study that helped prevent construction of a dam that would have harmed Botswana’s Okavango Delta, one of the world’s last great wetlands.

Part of what moved Mr. Scudder to go public with his revised assessment was the corroboration he found in a stunning Oxford University study published in March in Energy Policy. The study, by Atif Ansar, Bent Flyvbjerg, Alexander Budzier and Daniel Lunn, draws upon cost statistics for 245 large dams built between 1934 and 2007. Without even taking into account social and environmental impacts, which are almost invariably negative and frequently vast, the study finds that “the actual construction costs of large dams are too high to yield a positive return.” Read More

Mar 21 2014

1 Comment

Fit For Print – Did The New York Times Get it Wrong?

By Larissa Kyzer

Photos by Ólafur Már Sigurðsson

Tourism, it need hardly be pointed out, is big business in Iceland, an industry which in the years following the crash has ballooned, with more than double the country’s population visiting last year. But while making it into the New York Times would normally be good news for Iceland’s economy, a recent entry about Iceland’s highlands on the publication’s “52 Places to Visit in 2014” list was less than ideal from a publicity standpoint.

The paragraph-long blurb did mention the area’s unique landscape, but its key takeaway was that the “famously raw natural beauty” of the highlands—and more specifically, the Þjórsárver wetlands located in the interior—may not be enjoyable by anyone, let alone tourists, for much longer. As reads the article’s subtitle: “Natural wonders are in danger. Go see them before it’s too late.”

The suggested threat facing the integrity of Þjórsárver? Not impending volcanic eruptions or natural deterioration. Rather, the article stated that the Icelandic government recently “announced plans to revoke those protections” which had been safeguarding the wetlands, and additionally, that “a law intending to further repeal conservation efforts has been put forward.”

The “52 Places” article was widely quoted within the Icelandic media. Within days of its publication, the Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources issued a brief statement in Icelandic bearing the title “Incorrect Reporting by the New York Times.” It claimed that the New York Times article was “full of misrepresentations” and was “paradoxical and wrong.” The author of the article, contributing travel writer Danielle Pergament, was not contacted in regard to any “misrepresentations,” and neither was the New York Times—although the latter was invited to send a reporter to an open Environment and Communications Committee meeting on Þjórsárver a few days after the article’s publication.

So what exactly caused all the kerfuffle? Did The New York Times get it all wrong?

A Contentious History

Before we address the “incorrect reporting” alleged by the Ministry of the Environment, it will be useful to step back and explain a little of the context surrounding the Þjórsárver Wetlands and the battles which have been waged over this area since the 1960s.

Located in Iceland’s interior, the Þjórsárver wetlands stretch 120 square kilometres from the Hofsjökull glacier in the northern highlands to surrounding volcanic deserts and are characterized by remarkable biodiversity. A description on the World Wildlife Fund website points not only to the variance of the landscape itself—“tundra meadows intersected with numerous glacial and spring-fed streams, a large number of pools, ponds, lakes and marshes, and rare permafrost mounds”—but also to the area’s unique plant and birdlife, including one of the largest breeding colonies of Pink-footed Geese in the world.

Þjórsárver is fed by Iceland’s longest river, Þjórsá, which also sources much of the country’s electricity. Since the early 1960s, Landsvirkjun, the National Power Company of Iceland, has proposed several plans for creating a reservoir on Þjórsá that would facilitate increased energy production and enlarge energy reserves. Such reserves would not only be useful for existing industries, such as aluminium smelting, but—following the proposed creation of a submarine cable to Europe—could also be sold as part of foreign energy contracts as early as 2020.

Through the years, Landsvirkjun’s proposals have been met with frequent opposition, which in 1981 led to a nature preserve being created in the Þjórsárver wetlands. However, a provision was made within these protections, allowing Landsvirkjun to create a future reservoir, provided that the company could prove that the wetlands would not be irrevocably harmed, and that the Environment Agency of Iceland approved the reservoir plans.

By the late ‘90s, there was another flurry of activity: in 1997, the Iceland Nature Conservation Association (INCA) was founded with the “primary objective” of “establish[ing] a national park in the highlands.” Two years later, the government began work on an extensive “Master Plan for Hydro and Geothermal Energy Resources.” Divided into two phases that spanned from 1999 -2010, the Master Plan was intended to evaluate close to 60 hydro and geothermal development options, assessing them for environmental impact, employment and regional development possibilities, efficiency, and profitability.

Over the course of the Master Plan’s two phases, it was decided that the nature preserve established in the Þjórsárver Wetlands was to be expanded and designated as a “protected area.” The new boundaries were to be signed into regulation based on the Nature Conservation Act in June 2013 (the resolution was passed by parliament that year according to the Master Plan), until the Minister of the Environment, Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, elected to postpone making them official in order to consider a new reservoir proposal from Landsvirkjun.

Based on this new proposal, Sigurður Ingi has drawn up new boundaries for the protected area, which would expand the original nature reservoir, but cover less area than the original boundaries created by the Environment Agency of Iceland. The new suggested boundaries do not extend as far down the Þjórsá river, and therefore would allow Landsvirkjun to build their Norðlingalda Reservoir. Conservationists who oppose this point out that the three-tiered Dynkur waterfall will be destroyed if Landsvirkjun’s reservoir plans go through.

Parsing Facts

This brings us back the alleged “misrepresentations” in the New York Times write-up. Best to go through the Ministry of the Environment’s statement and address their qualms one by one:

“The article in question is full of misrepresentations about Þjórsárver preserve and the government’s intentions regarding its protection and utilisation. For instance, it states that Þjórsárver covers 40% of Iceland, while in fact, it only covers .5% of the country today.”

The first version of the article, since corrected, read as though the Þjórsárver wetlands constituted 40% of Iceland. In reality, it is the highlands that constitute 40% of Iceland’s landmass, and Þjórsárver is only part of this area. Following a call from Árni Finnsson, the chair of INCA who was quoted in the piece, this error was corrected.

“There are no plans to lift the protections currently in place. On the contrary, the Environment and Natural Resources Minister aims to expand the protected area and if that plan goes through, it’ll be an expansion of about 1,500 square kilometers, or about 1.5 % of the total area of Iceland.”

It is true that Minister of the Environment Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson has not suggested that the current protections—namely, the preserve that was established in the ‘80s—be altered. Nevertheless, it is also misleading to suggest that he personally “aims to expand the protected area,” as the expansion plans were basically mandated by the findings of the Master Plan. Moreover, he elected not to approve the Environment Agency’s expanded boundaries, but rather to propose new boundaries which would create a smaller protected area than was intended.

So no, Sigurður Ingi is not cutting back on “current protections,” but that’s only because he refused to approve the protections that were supposed to be in place already.

“Therefore, it is clear that there will be a substantial expansion of the protected area under discussion. The New York Times asserting that protections on Þjórsárver will be lifted in order to enable hydroelectric power development is both paradoxical and wrong.”

What we’re seeing the Ministry of the Environment do here is a neat little bit of semantic parsing. The NYT article states that after spending decades protecting the wetlands, “the government announced plans to revoke protections, allowing for the construction of hydropower plants.” This is a carefully qualified statement, and might accurately refer to any of several ministerial initiatives, from Sigurður Ingi’s redrawing of the Þjórsárver protected area boundaries, to his recent proposal to repeal the law on nature conservation (60/2013). This law was approved by Alþingi and was set to go into effect on April 1, 2014. It included specific protections for natural phenomena, such as lava formations and wetlands. In November, Sigurður Ingi introduced a bill to repeal the nature conservation law, although this has yet to be voted on by parliament.

So, no, the New York Times article was not “paradoxical and wrong.” It was, unfortunately, quite correct. Read More

Tom Albanese – Blood on Your Hands

On 6th March Tom Albanese, the former Rio Tinto CEO, was appointed CEO of Vedanta Resources, replacing M S Mehta. The newspapers are billing his appointment as an attempt to ‘polish the rough edges off [Anil] Agarwal’s Vedanta’ and to save the company from its current crisis of share price slumps, regulatory delays and widespread community resistance to their operations. This article looks at Albanese’s checkered history and the blood remaining on his hands as CEO of Rio Tinto – one of the most infamously abusive mining companies.

The Financial Times notes the importance of his ‘fixer’ role, noting that:

The quietly spoken and affable geologist is seen as someone willing to throw himself into engaging with governments and communities in some of the “difficult” countries where miners increasingly operate. That is something that Vedanta is seen as desperately needing – not least in India itself. Mr Albanese may lack experience in the country but one analyst says that can give him the opportunity to present himself as a clean pair of hands who will run mines to global standards…“There’s a big hill to climb there” Mr Albanese said.(1)

In fact Albanese has already been hard at work for Vedanta since he discreetly joined the company as Chairman of the little known holding company Vedanta Resources Holdings Ltd on Sept 16th 2013, billed as an ‘advisory’ role to Anil Agarwal (Vedanta’s 68% owner and infamously hot headed Chairman).

Vedanta Resources Holdings Ltd (VRH Ltd) (previously Angelrapid Ltd) are a private quoted holding company with $2 billion assets at present, and none at all until 2009. VRH Ltd own significant shares in another company called Konkola Resources Plc – a subsidiary of Konkola Copper Mines (KCM) – Vedanta’s Zambian copper producing unit. This is an example of the complex financial structure of Vedanta – with holding companies like this one serving to move funds, avoid taxation and facilitate pricing scams like ‘transfer mispricing’.

Shortly after becoming CEO of Vedanta Resources Holdings Albanese helped Agarwal by buying 30,500 shares in Vedanta Resources in November 2013 as their share price plummeted and Agarwal himself bought a total of 3.5 million shares to keep the company afloat. In December Albanese bought another 25,163 shares.

By February 2014 he was being sent out to Zambia to manage a crisis over Vedanta’s attempt to fire 2000 workers, which Agarwal himself had failed to fix during an earlier trip in November, and further damage caused by revelations about the company’s tax evasion, externalising of profits and environmental devastation in Foil Vedanta’s report Copper Colonialism: Vedanta KCM and the copper loot of Zambia.

In a taste of things to come newspapers referred to Tom Albanese as the Chairman of Vedanta Resources, and Labour minister Fackson Shamenda alluded to a ‘change of management’ giving them new confidence in Vedanta. Albanese appeared to have done some fine sweet talking, promising that workers would not be fired as part of a ‘new business plan’ and claiming that all of KCMs reports are transparent – an outright lie as their annual reports, profits and accounts are as good as top secret in Zambia and the UK.

However, scandals and unrest continued to blight Vedanta in Zambia and the Financial Times reported that Albanese had flown out a total of four times in February alone.

Albanese’s role as a ‘fixer’ and sweet-talker is nothing new. His appointment as CEO of Rio Tinto in 2006 was on very similar terms, as an article in The Independent newspaper noted his role to ‘green tint’ Rio, and ‘scrub its image clean’. The article mentions that, in an exclusive interview with the paper Albanese declared unprompted that the company is a “good corporate citizen”, and describes him showing no emotion and choosing his words carefully, focusing on safety and environmental and social responsibility.

But Albanese could not play dumb about the reasons a new image was needed for Rio. Since he joined the company in 1993 Rio had been accused and found guilty of a number of major human right violations.

In the early nineties they forcibly displaced thousands of villagers in Indonesia for their Kelian gold mine. They, and partner Freeport McMoran caused ‘massive environmental devastation’ at the Grasberg mine in West Papua, and when people rioted over conditions in 1996, began funding the Indonesian military to protect the mine. $55 million was donated by Freeport McMoran to the Indonesian military and police between 1998 and 2004, resulting in many murders and accusations of torture. In 2010 they locked 570 miners out of their borates mine in California without paycheques leaving them in poverty. In 2008 Rio threatened to shut their Tiwai point aluminium smelter, firing 3,500 if the government imposed carbon taxes. In Wisconsin, Michigan and California the are accused of toxic waste dumping and poisoning of rivers, and in Madagascar and Cameroon they have displaced tens of thousands of people without compensation or customary rights at their QMM mine, and the giant Lom Pangar Dam – built to power an aluminium smelter.

In 2011 a US federal court action accused Rio Tinto of involvement in genocide in Bouganville, Papua New Guinea, where the government allegedly acted under instruction from Rio Tinto in the late eighties and nineties when it killed thousands of local people trying to stop their Panguna copper and gold mine. 10,000 people were eventually killed in the class uprising that resulted from the conflict over the mine. Rio Tinto were accused of providing vehicles and helicopters to transport troops, using chemicals to defoliate the rainforests and dumping toxic waste as well as keeping workers in ‘slave like conditions‘.

Yet, Albanese is being seen as a respectable CEO with a more diplomatic and clean approach than his new Vedanta counterpart Anil Agarwal. There is great irony in Albanese’s promises to improve workers conditions in Zambia when Rio Tinto are famed for their ‘company wide de-unionisation policy’, with 200 people marching against the ill treatment of mineworkers outside the international Mining Indaba in Cape Town in February, calling them ‘one of the most aggressive anti union companies in the sector’.

Perhaps Albanese will feel at home in another company with a dubious human rights and environmental record. Both Rio and Vedanta have been removed from the Norwegian Government Pension Fund’s Global Investments for ‘severe environmental damages’ and unethical behaviour following investigations. The Norwegian government divested its shares in Rio Tinto in 2008, while it divested from Vedanta Resources in 2007, and also excluded Vedanta’s new major subsidiary Sesa Sterlite from its portfolio just a few weeks ago in January 2014.

Albanese was previously famed for being one of the highest paid CEOs on the FTSE 100, earning £11.6 million in 2011. However he refused his 2012 bonus in a last ditch attempt to save his career at Rio before he was fired in January 2013 amid a total of $14 billion in write-downs caused by his poor decision to acquire Alcan’s aluminium business just before prices crashed, and a $3 billion loss on the Riversdale coal assets he bought in Mozambique, making him in effect a ‘junk’ CEO today.

Other commentators have noted that this is not the first time Vedanta have recruited a junked mining heavyweight to save their bacon, but point out that the appointments have previously been short-lived, possibly due to frustrations about the dominance of majority owner Agarwal and his family. The infamous mining financier Brian Gilbertson, who merged BHP and Billiton, was another scrap heap executive who helped Vedanta launch on the London Stock Exchange in 2003 in the largest initial share flotation that year. However, he quit after only seven months after falling out with Agarwal.

Albanese is diplomatic when faced with questions about potential conflicts between himself and 68% owner and Chairman Anil Agarwal claiming Agarwal “will be in[the] executive chairman role when it comes to M&A and strategy”. However, commentators point out that, ‘the British Financial Services and Markets Act of 2000 stipulated that the posts of CEO and Chairman of companies should be separated – a principle which was backed in October 2013 by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority’, potentially posing another corporate governance issue for Vedanta, who are already accused of violating governance norms in London by people as unlikely as the former head of the Confederation of British Industry – Richard Lambert.

But Albanese is positive about his re-emergence as a major mining executive. In fact the man with so much blood on his hands may be alluding to his experience in making great profit from others’ misery, when he says to the Financial Times, on the occasion of his appointment as Vedanta CEO, that:

“Sometimes the best opportunities are when the times are darkest”.